The Colorful World of Jianzhan Glazes

Jianzhan bowls are mesmerizing for their dynamic glaze patterns—a fusion of soil and fire that created a rich legacy of ceramic artistry. First emerging in the late Tang through Five Dynasties era and flourishing in the Song Dynasty, Jianzhan was first documented by Song tea scholar Cai Xiang in the Tea Record, noting its maturity by the era of Emperor Renzong (1022–1063).

Why Jianzhan’s Glazes Captivate

Song literati favored simplicity and subtlety—values embodied by Jianzhan. Though seemingly plain, its intricate patterns and cozy, thick-walled design catered to the drinking culture of the time, especially for whisking powdered tea and organizing tea contests (‘doucha’). These bowls preserved heat well, revealed tea froth beautifully, and were easy to handle and drain.

Jianzhan and the famous Beiyuan tribute tea (from present-day northern Fujian) became inseparable symbols in Song-era tea culture. Emperor Huizong even praised the tea and bowl together in his Daguan Tea Treatise.

Glaze Types & Cultural Artifacts

Here’s a concise overview of key Jianzhan glazes and their cultural associations:

-

Hare’s Fur (兔毫, Tù Háo) — Featured fine streaks like rabbit fur and was the most celebrated glaze, dubbed “noble blue-black” by Huizong.

-

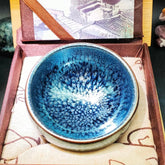

Oil-Spot — Metallic droplet patterns caused by iron crystallization and cooling fractures, often with reflective surfaces.

-

Black-Gold / Wujin (乌金, Gàn Hēi) — Opaque black bowls with subtle blue or brown tones and occasional streaks, reflecting kiln oxygen dynamics.

-

Partridge-Feather (鹧鸪斑) — Oval, pearl-like spots in gold or silver hues scattered across black glaze.

-

Golden Oil-Spot — Rediscovered in 2007 by master Huang Meijin, these modern bowls feature coppery-golden droplets achieved with innovative techniques (e.g., adding 24k gold).

-

Hao-Bian (毫变) — Rare “transforming fur” patterns, praised by Song scholar the Exemplified ‘Change’ in hare’s fur.

-

Yao-Bian (曜变, “Heavenly Variation”) — The ultimate black-glaze phenomenon, showcasing kaleidoscopic crystallization akin to stardust. While highly revered, only a handful survive from Song China. Kiln-recovered shards exist (e.g., Hangzhou), some matched to famous Japanese Tenmoku bowls.

Production & Clay-Vessel Pairings

Jianzhan’s perfection depends on temperature control, kiln atmosphere, and firing technique:

-

Wood-Firing in Dragon Kilns — Did not fully seal oxygen; position affected glaze outcome. The “xipao” (capped-fire box) technique stabilized cylinder heat. It also contributed to unexpected surface effects like “kiln tears” and color micro-variations.

-

Firing Temperature — Ranged from 1200–1350 °C. Lower temps produced red-orange (persimmon-red or shì hóng) glazes with metallic highlights from iron-manganese crystallization.

-

Surface Chemistry — Iron oxide content and reduction kept in precise windows triggered glaze crystallization—creating hare fur, oil spots, partridge feathers, or rare yaobian effects. Test-fire shards were used to monitor kiln conditions over multi-day firings.

Legacy & Resurgence

After centuries of silence, modern scholars and artisans revived Jianzhan techniques:

-

1979–81 Experimental Reproduction — Led to successful Song-style “hare’s fur” recreations. Today, electric kilns offer consistency, but many artisans still aim for the unpredictable beauty of wood-fired bowls.

-

Modern Fusion — Artists like Huang Meijin and Cai Zhigang introduced gold-drop and golden oil-spot glazes, blending tradition with innovation.

-

Cultural Renaissance — Linked to Chado (Japanese tea), YouTube and Instagram clips of Tenmoku bowls have fueled global Jianzhan interest.

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.