Yakishime vs. JianZhan: Two Visions of Fire and Clay

Across East Asia, the elemental forces of fire and earth have long shaped ceramic traditions that speak to philosophy, aesthetics, and ritual. Among them, Jian Zhan from China and Yakishime from Japan stand as two powerful expressions of what it means to shape meaning from clay. Though both are fired at high temperatures, their surfaces, textures, and cultural messages diverge like branches from the same ancestral tree.

Origins: Two Histories, One Fire

Jian Zhan: The Radiant Black Ware of the Song Dynasty

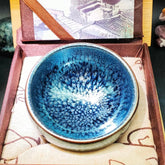

Jian Zhan (建盏) emerged during China’s Song dynasty (960–1279 CE) in the kilns of Jianyang, Fujian province. These bowls, crafted with thick iron-rich black glaze and fired in wood kilns, became the favorite vessels for “diancha” — a whisked tea preparation ritual among scholars and emperors. Their distinctive surface effects — like “oil spot” and “hare’s fur” — reflect both technical mastery and cosmic metaphor. Jian Zhan bowls were revered not only as teaware but also as artistic expressions of light within darkness, stillness within motion.

Yakishime: Japan’s Unglazed Voice of the Earth

Yakishime (焼締), by contrast, refers to a family of Japanese ceramics made without glaze, fired for days in high-temperature wood kilns such as anagama. Its name combines the verbs “yaku” (to fire) and “shimeru” (to harden). This technique, prominent since the 12th century, originated in utilitarian wares from the so-called “Six Ancient Kilns” (Rokkoyō): Bizen, Shigaraki, Tanba, Echizen, Seto, and Tokoname. Later, Yakishime gained new meaning when embraced by tea masters like Sen no Rikyū, who saw in their rough, scarred surfaces a perfect reflection of wabi-sabi — the beauty of imperfection.

Technique: Glazed Brilliance vs. Bare Flame

| Feature | Jian Zhan | Yakishime |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Treatment | Thick black glaze (iron-rich) | No glaze; natural ash effects |

| Firing Method | Wood-fired or reduction electric kiln | Long-duration wood firing (anagama, noborigama) |

| Visual Result | Lustrous, mirror-like, with patterned glaze effects | Matte, textured, with accidental fire and ash marks |

| Clay | Dense, iron-rich clay | Mineral-rich clay with feldspar, stones |

Aesthetic Philosophy: Brilliance vs. Simplicity

Where Jian Zhan evokes brilliance and introspection — capturing the cosmos in a teabowl — Yakishime reflects the landscape itself. Jian Zhan’s visual language is meditative and mesmerizing, celebrating change through glaze. Its beauty often lies in the mystery of crystalline eruptions on a glossy black field.

Yakishime, on the other hand, embodies restraint. Its textures are not added, but revealed through placement in the kiln, exposure to flame, and the unrepeatable actions of ash. The result? Earthy tones of red, brown, and ochre — marked with smoky shadows or flashes of green where ash has melted into the body. These are objects that quietly insist on presence, not perfection.

Contemporary Relevance: Revival and Innovation

The Return of Jian Zhan

In recent years, Jian Zhan has experienced a revival, both in China and globally. Artisans are pushing glaze experimentation, collectors seek rare “yao bian” (galactic shimmer) effects, and tea practitioners are rediscovering the tactile joy of these ancient bowls. New generations are merging tradition with modern form, making Jian Zhan part of contemporary teaware culture.

Yakishime Pottery in the Global Studio

Since the mid-20th century, Japanese potters such as Kaneshige Tōyō and Ueda Naokata IV began reviving Momoyama-period teaware. Western artists — including Peter Callas and Rob Barnard — studied Yakishime in Japan and brought its methods back to their studios. Today, Yakishime’s unglazed, elemental character speaks to those seeking authenticity, imperfection, and deep materiality.

Two Traditions, One Respect

Jian Zhan and Yakishime may look and feel different — one radiant, one raw — but both invite us into slower, more intentional moments. They ask us to touch, observe, and reflect. For the tea drinker, they are more than vessels; they are quiet companions that remind us: fire reveals, but never repeats.

At Porcelaire, we are inspired by both traditions. Our Jian Zhan teaware honors the black-glazed brilliance of Song dynasty craftsmanship, while our creative spirit remains open to the quiet power of unglazed form. In every bowl, there is fire, and in every fire, a story waiting to be touched.

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.