The Art of Firing Jian Zhan: Ancient Kilns, Modern Mastery

Introduction: Fire, Clay, and the Spirit of the Bowl

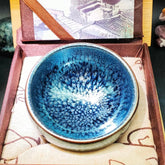

The beauty of Jian Zhan lies not only in its form and glaze but also in its fiery birth. The way a tea bowl is fired—through wood, flame, temperature, and atmosphere—determines everything: its texture, its color, and even its soul.

Traditional Wood-Fired Jian Zhan: A Battle with Heat

Firing Jian Zhan in wood kilns is a delicate dance with temperature. A difference of mere degrees can make or break the piece. Elements such as the oil content of the pine wood, its moisture, and even ambient air temperature all influence the kiln atmosphere.

To control this chaos, ancient artisans developed the “sagger” (匣钵)—a thick, funnel-shaped protective chamber placed around each tea bowl. It helped maintain stable temperatures and shielded the glaze from direct flame and ash.

The Dragon Kiln and Its Legacy

The dragon kiln, built along slopes, allows flames to travel through chambers in a wave-like motion. As the pine wood burns, it creates a strong reduction atmosphere—meaning low oxygen. This atmosphere is critical for forming famous Jian Zhan glazes like hare’s fur, oil spot, and black mirror (wujin).

-

Front of the kiln: high flame, high oxidation—ideal for hare’s fur.

-

Middle: stable heat, strong reduction—where oil spots may emerge.

-

Rear: lower heat, sometimes leads to unique, multicolored glazes.

But everything is a matter of chance. Even with the same clay and glaze, bowls fired in different sagger positions can yield dramatically different results.

The Ritual of Loading, Firing, and Cooling

Each sagger is carefully filled:

-

A layer of fine sand

-

A soft clay pad

-

A bowl placed upright on top

This prevents bowls from fusing with the sagger as the glaze flows down during high heat.

Firing takes 3–5 days, maintaining peak temperatures up to 1300°C (2370°F). Constant feeding of pine wood through kiln openings keeps the heat and reduction conditions stable.

After sealing the kiln, it cools slowly for several days. During this period, complex reactions between clay, glaze, and ash continue, birthing the signature patterns Jian Zhan is known for.

Kiln Trial Tiles: Ancient Quality Control

Ancient potters developed “test tiles” (试烧片)—small clay strips placed near viewing ports to monitor glaze transformation and kiln atmosphere. A valuable invention that increased firing success.

Even today, artisans often build small windows in their kilns to check the flame color and adjust conditions in real time.

Modern Wood-Firing: Dreams and Dilemmas

Reviving traditional Jian Zhan firing is a dream for many ceramicists—but it’s full of challenges:

-

Pine wood is costly and burns slowly

-

Kilns are massive and need constant upkeep

-

Yield is unpredictable and low

Despite these, wood firing is still revered for its ability to create irreplaceable glaze variations—from shimmering silver oil spots to fiery partridge feathers.

Electric & Gas Kilns: Precision and Possibility

While wood firing is full of risk and reward, modern kilns offer efficiency, control, and consistency.

-

Electric kilns are ideal for replicating complex glazes like yao bian (曜变)

-

Gas kilns can mimic reduction atmospheres with proper tuning

-

These kilns enable small-scale production with high success rates and minimal environmental impact

Most importantly, temperature and atmosphere can be digitally programmed, which means:

-

Even bubble distribution

-

More stable colors

-

Lower production cost

The Role of Pine Ash and “Kiln Sweat”

In wood-fired kilns, pine ash melts at high temperatures, fusing with iron in the clay to create “natural ash glazes.” These leave unique fire traces—known as kiln sweat—on the glaze surface.

Some artisans even grind old kiln walls into powder and add it to glazes. Rich in phosphorous and trace minerals, this creates stunning textures and depth.

One Kiln, Countless Colors

No two bowls are ever the same. Even in the same firing, glazes can turn:

-

Golden, silver, deep black

-

Flame-like red or smoky blue

-

Or a rare blend of all—just from subtle shifts in heat or wood placement

This randomness is the soul of Jian Zhan. It transforms pottery into a meditation on chance, time, and nature.

Conclusion: Firing Is Philosophy

Whether it’s the controlled precision of electric kilns or the unpredictable magic of dragon kilns, the art of firing Jian Zhan reflects a deep understanding of earth, fire, timing, and will.

Every tea bowl is a relic of heat, a memory of flame—and a quiet masterpiece shaped by the invisible hands of nature and man.

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.